Celebrating Black Businesses at Black History Month 2013 – Ade Sawyerr

Many things have been celebrated in black history month over the years but I doubt whether there has been any celebration of black people in business in Britain so in this brief note I intend to chronicle the history of black business development and celebrate the initiatives in the hope that more assistance will come in the way as we look forward to contributing to the brighter future of wealth creation in this country.

We have come a very long way from the days when black people did not routinely aspire or even think of self employment; setting up a business was but a dream for most.

I know there were several small black-owned businesses around 35 years ago, travel agents, hairdressing salons, night clubs, takeaways and restaurants, newspapers, patty shops and bakeries, records shops and various other businesses though most were devoted to personal services.

Research into black businesses

In 1980, the UK Caribbean Chamber of Commerce had brought their difficulties to the attention of government. The House of Commons Home Affairs Committee commissioned some research and called for several papers and published in December 1980 the report titled: West Indian Businesses in Britain.

Several others carried out research on the back of this initial report to assist in the development of policy on how black people in business in this country can be assisted.

- Martin Kazuka wrote ‘Why so few Black Business’ for the Hackney Business Promotion Project

- Alan Brookes researched Caribbean businesses in Lambeth

- Peter Wilson focussed on Brent for the Runnymede Trust in 1983

- Ade Sawyerr also contributed to the effort with my research on Particular problems faced by black controlled businesses in Britain with some proposals for their solution for his MBA dissertation at Manchester Business School in 1982 which broke academic ground on the subject.

Most of these reports revealed that black businesses faced several problems:

- Black businesses were small and remained so because they focussed on personal services serving a captive ethnic market.

- Access to capital and credit was difficult in the face of unwillingness by banks to lend partly because they did not understand the businesses and did not have confidence in them as entrepreneurs.

- There were problems with access to premises and skilled staff and competent managers

- Markets were generally closed to them because of their size and this led them to focus on their own communities.

These could be resolved with concerted action by government, the private sector and the academics working together and by facilitating organisations also providing assistance.

But it was left to Lord Scarmann who had been asked by government to inquire into the Brixton disorders who having found that ways of policing Brixton was totally unacceptable bemoaned the issue of young black people who were unemployed and to a large extent had no stake in the british society. He was bold enough to suggest a raft of employment training initiatives and went further to push government into action. Scarmann wrote …..: but I do urge the necessity for speedy action if we are to avoid a perpetuation in this country of an economically indisposed black population. A weakness in British society is that there are too few people of West Indian origin in the business, entrepreneurial, and professional class.

True to form there were several initiatives directed at resolving some of these problems. The main thrust of the initiatives were in

- Premises and general assistance to business people

- Business skills training and employee training

- counselling and consultancy services to develop business plans

- finance in the form of loans and grants

- Building capacity to ensure that businesses can tender for contracts

General Assistance and premises

The Economic Development Units of most local authorities employed Ethnic Minority Business Officers to help identify businesses who could be assisted with grants and premises. The main policy used was the Inner Urban Areas Act that allowed local authorities to boost business development in local areas by giving start up businesses rent and rate grants as well as premises improvement grants. There were economic development units in most areas with a larger than average black population including, Lambeth, Brent, Hammersmith and Fulham, Haringey, Hackney, Camden, Waltham Forest, Southwark, Lewisham, Greenwich, Kensington and Chelsea.

These officers also led in the mapping and creating of directories of black business enterprises that formed the basis for the setting up of black business development associations in various boroughs. These organisations became the central point of focus for the development of further initiatives that would help the black entrepreneurs. These helped also with signposting prospective black businesses to existing assistance measures and helped to form a lobby for more packages to support local business in the early to mid 1980. some major players then were, Manny Cotter, Orin Miller, Mark MacArthur, Benjamin Smart, Desmond Shields, Henderson Darlymple, Ionie Richards, Winston Collymore, Wyn Knuckles.

GLC helped with advice and funding for cooperatives setting up many black led Cooperative Development Agencies.

In addition with these economic development units, the GLC at the time helped in the establishment of various cooperative development units in different parts of the London. The belief then was the black people were more suited to alternative methods for doing business and therefore a cooperative structure were labour employed capital and where democratic decision making within a non hierarchical work environment with people with different skill sets sharing the surpluses equally was more appropriate. These officers of the black cooperative development movement were an energetic bunch of advisers who formed themselves into a group Kala Ujamaa. Some players were Kwaku Ampomah, Wendy Campbell, Moses Sithole, Hilary Banks, Cynthia Barnes, Steve Cole, Knox and several others.

But there were several other initiatives led by black people that complimented the efforts of the local authorities. For instance, there was New World Business Services set up by Jonathan Emanuwa and Devon Thomas and Paul Bogle Enterprise Trust that had been set up by Bunny Barnett; both these however benefited from support from facilitating agencies and the Greater London Council at the time and like everything else the funding did not last for one reason or another.

In 1984, The Greater London Enterprise Board set up a scheme for Business Consultants from the Black community to assist in the preparation of business plans and set aside grants to match funding that these deserving businesses would receive from banks under the government Loan guarantee scheme. GLEB commissioned Equinox Consulting to work on a demand survey to test the feasibility of an African Caribbean bank but the whole scheme was riddled with diversions about the profitability of such a bank and was eventually smothered by the involvement of mainstream consultancy who said ostensibly donated their time free of charge but ended up putting so many obstructions in the way the bank should work.

Training

The Manpower Services Commission led in business providing access to business skills training to prospective and existing businesses and their staff. There were several training programs that were implemented mini business programmes organised over weekends, start up business programmes to increase the rate of business start ups. The objectives were essentially to get people who attended to start up in business immediately. Equinox Consulting were contracted to run some of these courses consisting of seven sessions run over 4 weekends that enabled the participant to draw up an outline of a business plan. This was at the time of massive unemployment in Britain and though the objectives of the Thatcher government in sponsoring these programmes was to encourage more people to set up in business and create private sector jobs, for a large number of black people who attended the courses, it was a bout the preparation towards their future intention of setting up in business.

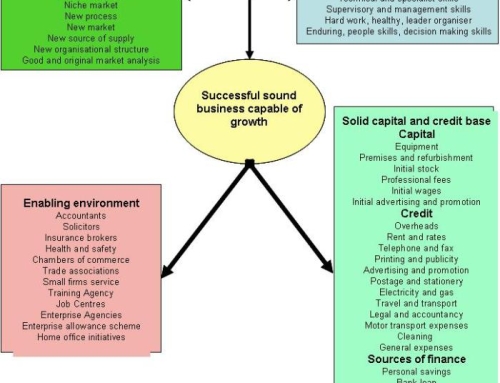

But working with black businesses in the early to mid 1980s had its challenges. There were several with sound business ideas who did not have the financial capital or credit to set up in business at the time. They also lacked the management skills necessary to make a success of the business. Most were working in relatively low paying jobs, but a few professionals needed the knowledge of what they should do if they were made redundant or wanted to branch out on their own.

In addition to the provision of business skills training for the entrepreneur to get them to understand the basics of business and be able to talk the language of the banks and the suppliers, there were other training programmes that were set up, Training for Work Programmes that were handled by the successor bodies to the Manpower Training Commission, the training commission, the training agency, the training and enterprise boards and the learning and skills councils. Several black organisations were involved in providing these training courses in the inner urban areas and Equinox Consulting delivered

By 1985 the government in association with some facilitating agencies and mainstream private support set up black-led Enterprise Agencies in Manchester, Deptford, Birmingham, Bristol, Wandsworth, Tottehnam, North London, Nottingham to continue with the work of providing much needed support but also in trying to open up markets.

There were other initiatives in business as well as in employment.

Shell set up Livewire, the Princes Trust and Business in the Community got involved and set up the Black Secretariat and DTI set up the Black Business Development Initiative to try and assist with coordination

The Greater London Council had caught on to the idea of how to change the labour market in the hope that their actions would improve access to the job market for black people in Britain, measures that the believed would eventual ensure the promotion of more black people in the job place. Their contract compliance measures were aimed at requiring firms contracting with the GLC to show that they were equal opportunities employers. The scheme would have been extended to getting these firms to include minority contractors in their contracts by sadly the demise of the GLC meant that those measures were still born and the issue of contract compliance was sadly replaced by compulsory competitive tendering by the local authorities that did not have the same effect.

After the 1987 elections many more black led assistance programme were set up. The Inner City Taskforce Initiative, the City Challenges, Single Regeneration Budgets that became the Neighbourhood Renewal Fund.

The 80s were abuzz with a lot of assistance programmes for black businesses though not all well coordinated. What this country needed most at the time was a Minority Business Development Agency, like the agency that operates in America, to provide a coherent strategy.

Procurement assistance

By early 1990, the emphasis had shifted from the setting up of more black businesses to the thorny issue of how to open up markets to small black businesses and how they will be fit to supply goods.

Procurement Assistance became the order of the day and the setting up of several black business associations that would provide effective networking to ensure that businesses would meet with the right type of suppliers that would give them contracts or they could benefit from tendering for government contracts.

The markets never really opened up and but some black businesses such as Dyke and Dryden, Val McCalla with the Voice Newspaper that provided so much opportunity for black journalists to hone their skills and Neil Kenlock and Patrick Berry of Choice FM are much to be applauded for their success. But these served captive ethnic markets.

The employment initiatives must have paid off, because in the last decade, with the changing dynamics in businesses from production based to skill and knowledge based, we have a different type of black entrepreneur.

These have benefitted from jobs at senior levels so they can manage their businesses better. Most of these have worked in skill based jobs and then used their experience and expertise to branch out on their own. The new black business person has expertise in management, can talk finance and knows the intricacies of production and service management and is able to apply all the social marketing and web based tools available to get a quality products or services to a client or customer be they small or large. They have sophisticated business models with huge doses of disruptive technologies and innovation and counter intuitive strategies and with that has come a different more positive can do attitude. They are bolder and younger and ready for the cross over into mainstream markets.

Finance is less of a barrier now that we have Dragons Den, various venture capital funds and latterly crowd funding.

But the markets are still very much closed to a lot of black businesses as they are excluded from the networks where large deals are cut. The blocks remain because black businesses are still being denied access to markets and networks, they are being denied access because the procurement processes still work against small businesses which is why the bundling of contracts must be dismantled and replaced with bitesize lots and contracts, that small businesses especially black ones can hope to bid for and win.

So perhaps now is the time to give black businesses another push – to consolidate the successes of the past and use the power of government to create that enabling environment to give black businesses a fairer chance of winning contracts from the public sector.

So when the government considers setting aside 25% of contracts to small businesses, it must indeed consider whether black businesses can be given access to at least 10% of these contracts. It would not be so uncompetitive an advantage indeed it would be just reason for the accelerated development of black businesses that will be the businesses of the future for London and this country.

I am sure that the mayor is listening to this now that we are in his den.

If I started by saying – look how far we have come, it is because I have the confidence that with the help of facilitating agencies, bigger businesses, financial institutions and a fairer stab at winning contracts from government that we will go even further. If I started by saying the glass was half empty, it has moved from being half empty to half full. But how do we get the glass full?

After all the hard work of the past generation, black businesses need all the help they can get. Some call it luck that arises out of opportunity that the longer you stay in business despite all the tribulations, the more you become patient and with patience comes experience and with experience comes hope that there will be a brighter future, much more prosperous than the past.

Let me end this with the words of a favourite song by Osibisa – Woyaya

We are going – Heaven knows where we are going

We will get there – Heaven knows how we will get there

It will be hard we know – And the road will be muddy and rough

But we’ll get there – we know we will

Please watch the video – Black History Month Debate at the Mayor’s Den

– http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EVIel0ScHV0

Great!