‘Africans Were In Britain Before The English…’

This powerful statement of fact is how historian Peter Fryer started his seminal book Staying Power (Pluto Press, 1984) documenting the black presence in Britain

Posted in Voice Newspaper 28/12/2015 10:00 AM

SONGSTRESS: An unnamed member of The African Choir from South

Africa who played concerts for a high-profile audience including Queen Victoria, courtesy of Hulton Archive/Getty Images

IT IS a notion that would confound most people, particularly against the backdrop of today’s fierce debate on migration. Yet the truth remains that African history in Britain stretches back to the 3rd Century when valiant and gallant soldiers fought beside the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius.

Though a few of these largely forgotten heroes remained in England, Scotland and Wales, the focus has been on Africans as slaves and servants in royal courts in the stories of people like Quobna Ottobah Cugano, Olaudah Equiano and others who documented their lives in Britain.

After the transatlantic slave trade, Africans started coming to this country as much sought-after musicians and performers in the courts of nobility. Others came as seafarers working on ships that brought raw materials from the colonies to Britain and returned with finished goods fashioned for the tropics.

They settled mainly in the port towns of Bristol, Liverpool and Portsmouth and through the advent of colonialisation others were brought here to learn the language so that they would act as interpreters to aid trade with Africa.

African migration trickled through the 17th Century though, by the end of the 18th Century, the numbers of Africans in Britain had swelled to more than 15,000.

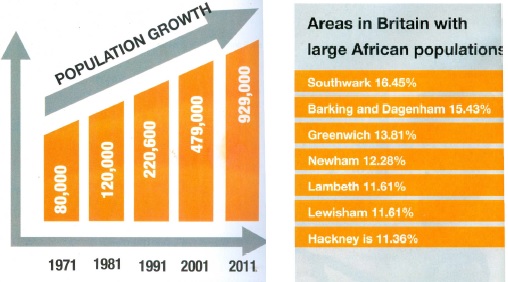

This is a far cry from the accelerated pace of migration in recent years from an estimated 80,000 in 1971 to 120,000 in 1981, 220,600 in 1991, 479,000 in 2001 to its present level of 929,000 in 2011.

Education is still the main pattern of migration of Africans to Britain as revealed in a recent survey of Nigerian Health and Education Professionals in the UK for the International Organisation of Migration.

Equinox Consulting found that a large number of professionals had actually been born in the UK and had been taken home to Nigeria for their secondary and sometimes university education.

The pull factors that had brought them into Britain were to improve their educational qualifications and to seek better economic opportunities.

Their continued stay was more a result of the lack of opportunities for professional advancement ‘back home’ owing to a lack of infrastructure and an enabling professional environment.

COLLECTION: Coins showing Roman Emperor Lucius Septimius Severus, courtesy of the Black Cultural Archives

In late 19th Century and early 20th Century, there is evidence that large numbers of students came from the colonies to study as administrators, technicians and professionals (lawyers, doctors, nurses, surveyors, engineers, teachers and several others) who were brought by the colonial government or sponsored by their parents and relatives These larger numbers brought with them the need to organise and fight for their welfare and against racial injustice in Britain.

The West African Students Association was one such organisation formed in the early 1920s to promote African nationalism and Pan Africanism.

By 1945, WEB Dubois and George Padmore had moved for the hosting of the 5th Pan-Africanist Congress in Manchester that saw a large number of future politicians who led African countries to power attending: Jomo Kenyatta, Kamuzu Banda, Kwame Nkrumah, Obafemi Awolowo, ITA Wallace Johnson, Jaja Nwachuku amongst others.

MEETING OF MINDS: Pan-African Congress Delegates in Manchester, courtesy of GM Lives

The activism and organisations continued under the Africa Centre set up in the 1960s as a place for African students and professionals to meet, be informed about what was happening in their countries, socialise and be entertained.

Most of these students went back home to work in their newly-independent countries whose governments continued to send students to Britain to study and return to help in running their countries.

However, by the 1980s, the pattern of migration changed, fuelled by the frequent military interventions and civil wars that plagued the continent and led to more people seeking political asylum, fleeing war-torn countries. More people migrated as economic refugees because their countries and livelihood had been destroyed by political mismanagement.

The Eighties and Nineties saw a swell in migration from countries such as Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Zimbabwe and also from Somalia, Eritrea and Ethiopia.

Increasingly, however, there are more migrants in Britain from the French-speaking countries in Africa, such as the Congos and Cote D’Ivoire.

Today, the numbers seeking asylum has tapered off and many of those who migrated to Britain for economic reasons are returning to their homeland despite the established African community spanning over four generations.

GET TOGETHER: Gorgeous guests at the Africa Centre’s annual festival, courtesy of Press Association

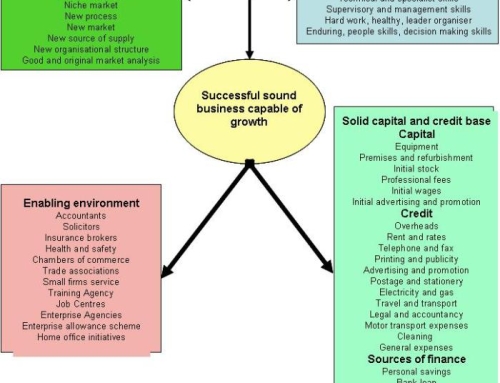

What is known about the African population is that those who have come mainly as economic migrants are working in elementary jobs while those who have come to study are in professional jobs.

There are now seven areas (by local authority) in Britain where the African proportion of the population is more than 10 per cent, such as the London borough of Southwark, which is the highest at 16.45 per cent.

More and more African people are however moving further away from London either as a consequence of the dispersal policy championed by the Home Office in the Nineties or by professionals moving further afield to take advantage of the benefits of better facilities for families in the suburbs.

The life of the African over the years has been of immense benefit to Britain and its political, social and cultural diversity.

As politicians, academics, professionals, business people, sports personalities and musicians, they are in the private sector, the public sector and the civil society sector and it makes one wonder what would happen if they were all enticed back to their country of origin.

Would Britain as we know it survive? Or would it be best for those countries in Africa if they find a much better way of getting all this large pool of talent back to help their countries?

Ade Sawyerr is a partner at Equniox Consultancy, which focuses on social and economic issues affecting disadvantaged communities in Britain. He specialises in the social, cultural and political issues affecting the African diaspora.

Leave A Comment