The African Or Black Question: Colour or Heritage? – Ade Sawyerr

In an article I wrote last year, I wondered what people of African descent would make of the declaration of 2011 the International Year for people of African Descent, http://www.obv.org.uk/news-blogs/2011-year-people-african-descent, and to what extent they would benefit from the message of recognition, justice and development that was intended to be the hallmark of the celebrations. Though we are yet to evaluate the significant outcomes of the year of celebration, it has forced on us a question that is being asked about what people of African descent should be called in the Diaspora – ‘The African or Black Question’?

Questions of identity are complex, sensitive and personal, and therefore reaching consensus even after extensive discussion may be difficult. Any answer must be well reasoned and cover issues of race, ethnicity, culture, changes in terminology and colour. My conclusion after considering this issue is that the colour Black does not quite denote our identity in Britain and that our heritage and historical geography, African is a more enduring and fitting term for our identity as a people.

Race and ethnicity

There is only one human race, homo sapiens or humanity as recent advances in DNA technology have confirmed, but the quest for developing a hierarchy of the species continues with classification into different groups or races and given rise to several theories of race none of which have stood the test of rigorous analysis.

The ‘three race theory’ asserts that there are three main races – Negroid, Caucasian and Mongoloid; the ‘geographical theory’ postulates that race is dependent on where your origins are in the world – Africa, Europe or Asia; the evolutionary theory explains the possibility that the distinguishing physical features on which race is based, the colour of the skin, texture and colour of hair, shape and colour of eyes and shape of noses, may have been acquired because of the need to adapt to their environment. Other theories have as much as 40 sub-races and in Africa with varied geography and diversity in physical appearances, sub Saharan Africa alone has 9 sub races Capoid, Khoid, Sanid, Congoid, Nilotid, Aethoid, Sundanid, Babutid, and Kafrid.

This proliferation of sub-classifications calls into question the use of physical features as the main basis of race classifications. Indeed race cannot explain widely differing body features even in the same family. Some people are tall, some are short, and some have lighter or darker complexions or different eye, hair and skin colour. Indeed some Europeans have darker complexions than some light skinned Africans.

Another difficulty of race is the temptation by some experts to link race with intelligence in order to justify the hegemony that leads to racial discrimination. It was this tenuous link that caused the United Nations to raise ‘The Question of Race’ and conclude that perhaps ethnicity was a better and less emotive determinant of group identity. Section 6, the relevant portion of their statement issued on 18th July 1950 reads

National, religious, geographic, linguistic and cultural groups do not necessarily coincide with racial groups: and the cultural traits of such groups have no demonstrated genetic connexion with racial traits. Because serious errors of this kind are habitually committed when the term “ race ” is used in popular parlance, it would be better when speaking of human races to drop the term ” race ” altogether and speak of ethnic groups.

However, ethnicity, of which there are more than 5,000 groupings in the world, also has pejorative content and does not necessarily lead to objective classification. Ethnicity evokes images of a pagan and heathen nature of those to which they refer; their nationalities, heritage, language, religion, ideology, ancestry, homeland, tradition, food, clothes, geography and culture are still seen as exotic and ethnic relations are noted mainly for being underpinned by tensions that have led to war in Eastern Europe and riots in England.

Race, classification and discrimination

In Britain, race as defined by The Race Relations Amendment Act 2000 includes a) colour, b) nationality and c) ethnic or national origins. The Act calls for positive action measures that would eradicate racial discrimination and there is a requirement of ethnic monitoring based on 17 classifications. These classifications are, unsurprisingly, based on race, nationality and colour are also used for the census.

| White | British | Irish |

Any other White background |

|

|

Mixed |

White and Black Caribbean |

White and Black African |

White and Asian |

Any other Mixed background |

|

Asian or Asian British |

Indian |

Pakistani |

Bangladeshi |

Any other Asian background |

|

Black or Black British |

Caribbean |

African |

Any other Black background |

|

|

Chinese or other ethnic group |

Chinese |

Any other ethnic group |

||

|

Not stated |

||||

Most people of African and Caribbean descent born in Britain accept that they are British, the classifications do not mention English or Welsh which denote ethnicity, but there is mention of Black and White but no mention of Yellow.

Race, colour and identity

In the three race theory, the only mention of colour is Negroid and in the theories that provided many sub races, there is no mention of any colour and so we have to wonder why colour has been used to denote races. For instance Negroid or African is equated with Black, Caucasian or European is denoted as White, and Mongoloid or Asian was classified as Yellow. The truth is that there is nothing White about Caucasian, it is a reference to a mountain in the Caucuses somewhere in the old Soviet Union where the skull of a person was noted to be typical of all Europeans and Mongoloid was a description based on what people with Down Syndrome were supposed to look like and used to describe Asian looking people; the term Yellow has fallen into disuse so why do we still hold on to the terminology of the past in equating colour with race unless the fact of translation of Negroid into Black allows us to hold on to a pejorative view of our race.

Negro was used in America for centuries but the pejorative use of Nigger caused a shift away from Negro to Coloured though some notable institutions such as the United Negro College Fund retain the name which is a throwback to the days when Negros were educated separately. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the most authoritative and preeminent organisation formed during the period when ‘coloured’ was seen as more progressive retain it in their name. The term ‘Coloured’ gave way to Black in the 60s and 70s, fuelled by the need to reclaim the heritage and transform it into a positive symbol of pride.

The term Black rode on the back of the Civil Rights protest movement. Black Power was at its peak, with the Black Panthers, the Black salute by Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Olympics, in the song ‘Say it loud, I am Black and Proud’ by James Brown, the Big Afro and the dashiki were seen as positive manifestation of their African identity. The Black Congressional Caucus remains as a vestige of this period.

It was not only in America that the terminology of identity has been shifting; there are notable examples from Africa too. In South Africa, Steve Biko propounded a Black Consciousness Movement that took pride in the culture and was developed in apposition to the Bantu education that was provided under apartheid. This movement was within the context of South Africa where the African National Congress espoused a non-racial view of their protest. It is this non racial view that caused the Pan-African Congress and Azania Peoples Organisation to breakaway from the ANC.

Leopold Senghor of Senegal, Aime Cesaire of Martinique and Leon Damas of French Guiana provided a philosophical framework for black politics and ideology as a protest against cultural and colonial racism, Negritude. Their Negritude movement however became much derided. Some of the arguments against it then were:

a) In the common bond of an African heritage, a colour Black, was not sufficient as a concept to fight racism.

b) Too much colour, Black, was unlikely to achieve anything except draw attention to a defensive projection of what you really do not want to be.

c) The word Black had always been used as a derogatory term to describe people of African descent, there was no need to reclaim it.

d) Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka commented, “A tiger does not proclaim his Tigertude, a tiger pounces on its prey”.

e) Negritude sounded so close to ‘nigger’ that it could only be seen as ‘nigger with attitude’.

People of African descent in Britain have gone through similar shifts in terminology. In the 1950s and 1960s, we were defined mainly by our colour and referred to as Black or Coloured.

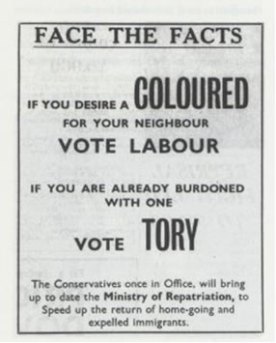

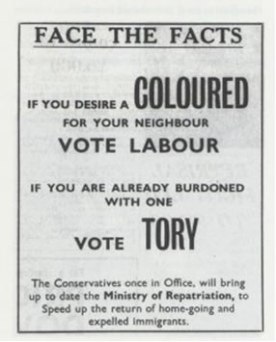

A 1964 Lambeth Election poster sponsored by the Conservative party used the then acceptable word ‘coloured’ but with very inflammatory language

We have also been called African, those of us from the Caribbean have been called West Indian and Afro-Caribbean, and now African-Caribbean became a more acceptable term of description. There are also some who do not want the term Black and have suggested different terms of ‘endearment’ or ‘affection’ such as Afro-Saxon or Afropean.

Black as an inclusive political term

While the term black had been adopted in America for reasons of pride, in Britain the term was adopted within the framework of the Negritude movement as a conscious political and anti racist term to denote all people of colour or non white people as well as people who were not part of the dominant Anglo white culture. So black was embraced by Asian people as well as Chinese people and even to an extent by the Irish. It was meant to embrace all the politically oppressed.

In 1983 however the two dominant political parties rejected the term Black coincidentally for the same reason. The Labour Party rejected Black Sections for being too divisive, outlawed it and refused to support any candidate chosen by them. The Conservative Party came out with a bold election poster of acceptance of Coloured people, rejecting the term Black as an unworthy and politically incorrect Labour Party construct.

The poster may have helped the Conservatives in 1983 but it could not wish away the race discrimination suffered by Lord Taylor when he was rejected a decade later by his own party in 1993, because he was not British enough.

Though several organisations still bear the term Black, Black as a political term has been diluted considerably over the years. It was conjoined with Minority Ethnic to become BME or black and minority ethnic; it has now moved on to BAME to denote, Black Asian and Minority Ethnic and extended to BAMER to cover refugees.

The Black in BME is now essentially African and Caribbean, so why do we not just accept ourselves as African Caribbean Asian Minority Ethnic, (ACAME), a bit of a mouthful, but at least we do not have to persist with a term, Black, that has become meaningless. In the 21st century there are several people who are uncomfortable with the politics of protest and would wish to move to project their true positive heritage. They do not want to be held hostage in a solidarity movement that provides them with no benefit and is only a convenience for some.

Colour or geographical and historical heritage

Black as a political term really no longer serves our purpose and we need to return, not to ethnicity or race or culture or skin colour but to our origins to define who we are. African, which is our heritage resounds better if it is to help us define our identity, the other terminologies will not go away but with time being of African descent or heritage will take over and be acceptable especially as Africa moves out of the hopelessness of foreign domination and globalisation.

Kwame Nkrumah provides us with a more fulfilling political concept on which to base our identity. He adopted the Black Star of Marcus Garvey into the Ghanaian flag, and named his shipping company the Black Star Line. This was in support of Pan-Africanism as the identity and ideology for all people of African descent making common cause with the brothers and sisters in America and the Caribbean. The concept of Pan-Africanism better represents who black people of African descent really are.

I suspect that there will always be lingering doubts and objections along the way. It took some time for some to accept the term African to embrace people of African descent in America but eventually the issue was settled and people of African descent in America whether they were born in Africa, the Caribbean or America now prefer to be called African Americans much in the same way that there are Anglo-Americans and Italian Americans and Chinese Americans. They have embraced African and the issue settled.

There are those of Caribbean heritage who believe that the term African does not describe them very well and in the same mode of ‘divide and rule’ see nothing African about them. They should however be reminded that in their own countries of origin in the Caribbean, they are identified as being from the African ethnic group co-existing with Arawaks, Caribs, Indians, Chinese and European. There are probably more people from the Caribbean in America than in Britain since Britain stopped being the preferred choice for emigration, but these Caribbean Americans have now embraced the term African American if even after some resistance. So perhaps African Caribbean in the Britain may also consider this identity and let it grow on them.

Will adopting African dispel all the negative notion of Africa as a no hope continent and will it prevent the present onslaught of attacks on other cultures that are seen to be ‘contaminating’ the existing British culture. Black, African and African Caribbean culture presents a baggage, it is seen as nihilistic and inferior to some, it is what the authorities perceive as the reason for our over representation in things that are not progressive in society but under represented in the positive things. This onslaught on multiculturalism as a non desirable import into this country refuses to recognise that there are already different cultures within this country and the Scottish, Irish and Welsh want to project their own culture even if they continue to be part of the union.

There is no doubt that people of African descent are also British, it is not about the nationality and though they are excluded from the mainstream ethnicity of the nations – I am yet to hear the term Welsh Black or Scottish Black or English Black or indeed Irish Black gain currency and yet there are many young sports people of African heritage who represent the British Isles in major sports.

Reclaiming our African Heritage

Will The African or Black Question, though important to ask help people of African descent in this country in any meaningful way? I think that it is a start of claiming our heritage and a start of defining for ourselves who we really want to be; I think that is important and I think that being an African has sufficient positive points if we are prepared to work on it. Agreeing on what we call ourselves will only work if we are able to combine with this a certain pride of knowing who we are, but it will also come with some form of negotiation.

Perhaps, this is the time that people of African heritage should define themselves much in the same way as American people of the same descent and heritage embraced the continent which is the source of all humanity. If we need an all-encompassing term to define who we are, African without the Black is more helpful and I will agree with the United Nations that the International Year for People of African Descent was certainly a better description of this celebration than International Year of Black People.

I suppose that as a Pan-Africanist whose heroes came from the continent of Africa, such as Nkrumah and Nyerere and the Caribbean such as Padmore and Garvey and America, such as DuBois and Booker T Washington, I can endorse the term African-British.

“I have no wish to be the victim of the Fraud of a black world.

My life should not be devoted to drawing up the balance sheet of Negro values.

There is no white world, there is no white ethic, any more than there is a white intelligence.

There are in every part of the world men who search.

I am not a prisoner of history. I should not seek there for the meaning of my destiny.

I should constantly remind myself that the real leap consists in introduction invention into existence.

In the world through which I travel, I am endlessly creating myself.” (Fanon in Black Skin, White Masks, 1952)

Ade Sawyerr is partner in the diversity and equality focussed management consultancy, Equinox Consulting. He can be reached at www.equinoxconsulting.net

I think this is a debate we, peoples of African heritage must have pretty soon. One thing know is, if you fail to properly define yourself-who are, what you are and what you want to be, it’s like leaving your fate for other people to decide and grumble if they get it wrong.